|

HIP DYSPLASIA

Hip Dysplasia is a common condition of large breed dogs and many dog owners have heard of it but the fact is that anyone owning a large breed dog or considering a large breed dog as a pet should be become very familiar with this condition. The larger the dog, the more likely the development of this problem becomes, particularly as the dog ages and loss of mobility/arthritis pain become important life quality issues.

The following is a review this disease in the form of an FAQ. If you have additional questions, please use the email function listed on this page to forward them. New questions and their answers may be added to this page.

|

SO WHAT IS “HIP DYSPLASIA”?

The term “dysplasia” means “abnormal growth” thus “hip dysplasia” means abnormal growth or development of the hips. Hip dysplasia occurs during the growing phase of a puppy, usually a large breed puppy, and essentially refers to a poor fit of the “ball and socket” nature of the hip. The normal hip consists of the femoral head (which is round like a ball and connects the femur to the pelvis) as well as the acetabulum (the socket of the pelvis), plus the fibrous joint capsule and lubricating fluid that makes up the joint. The bones (femoral head and acetabulum) are coated with smooth cartilage so that motion is nearly frictionless and the bones glide smoothly across each other’s surface.

|

The femoral head (the ball in the ball and socket joint) is outlined in yellow.

The acetabulum (the socket in the ball and socket joint) is outlined in red.

The femoral head “ball” is designed to fit inside the acetabulum “socket.”

|

|

For more detail on the structures of the normal joint click here.

When a dog has hip dysplasia, the ball and socket do not fit smoothly. The socket is flattened and the ball is not held tightly in place thus allowing for some slipping. This makes for an unstable joint and the body’s attempts to stabilize the joint only end up yielding arthritis.

IF THIS DISEASE STARTS IN PUPPYHOOD WHY ARE MOST AFFECTED DOGS ELDERLY?

Actually, there are two sets of patients typically affected by hip dysplasia. The first affected group is the adolescent dogs, typically 6-18 months of age. The radiograph on the right above shows the hips of such a patient.

|

Radiograph of a Labrador retriever puppy's hips Radiograph of a Labrador retriever puppy's hips

showing hip dysplasia but no arthritis change.

Note how the hip socket is flattened and the femoral heads do not fit snugly.

(Photocredit: Joel Mills via Wikimedia Commons)(original graphic by marvistavet.com) |

|

This dog has hip dysplasia but has not yet developed arthritis. Note the shallow hip sockets. Dogs in this group are commonly brought in for signs of discomfort. Radiographs are then taken and hip dysplasia is discovered. Many dogs with similar radiographs will not be in pain and thus will not end up coming to the vet for an evaluation. These dogs show up later as elderly dogs, after they have been walking on their poorly formed hips for many years. After many years, bony spurs along the margins of the socket, mineralization of the joint capsule, cartilage wear, and inflammatory change in the joint (i.e. degenerative arthritis) have become painful and now the dog comes to the vet for an evaluation. The radiograph on the bottom right shows extreme degenerative arthritis. Notice how the femoral heads look like clubs.

|

After years of walking on dysplastic hips,

severe hip arthritis is present in this patient.

(original graphic by marvistavet.com)

|

WHY DO SOME DOGS HAVE PAIN AT A YOUNG AGE WHILE OTHERS DO NOT HAVE PAIN UNTIL THEY ARE OLD?

Obviously different individuals may have different degrees of dysplasia. A dog’s weight makes a difference (a lighter dog can tolerate a more abnormal hip joint). The muscle mass supporting the joint is greater in a younger dog and helps reduce the stress directly on the bones. Still, some dogs have truly shocking radiographs and virtually no symptoms while others show relative subtle changes and are very uncomfortable. It is not known why there is not a better correlation between radiographs and actual pain.

HOW CAN AN OWNER TELL IF THEIR DOG IS HAVING DISCOMFORT?

Do not expect a dog with dysplasia (or any other chronically painful condition for that matter) to cry or whine in pain. Instead discomfort is shown with reduced activity, difficulty rising or lying down or going up stairs. A characteristic swivel of the hips is seen from behind and classically stairs are taken in a “bunny hop” fashion.

WHAT CAUSES HIP DYSPLASIA?

The primary cause of hip dysplasia is genetic but inheritance of this trait is not as simple as a dominance/recessive relationship like we study in high school biology. Normal dogs can breed and yield dysplastic offspring as the condition may skip generations. Further, dogs with a genetic picture conducive to hip dysplasia development still must contend with other factors such as level of exercise at an early age, nutritional factors, hormonal/neutering factors, and other environmental situation.

Prevention of hip dysplasia primarily focusses on breeding dogs with normal hips. The problem with this is that dogs often do not develop signs of hip dysplasia until well after they have been bred. A genetic test would be of great value in dog breeding but presently there is only such a test available for Labrador retrievers (through Idexx laboratories); identification of dogs with less than stellar hip quality so as to exclude them from breeding is done via OFA and PennHip certification (see sections on registration below).

It is important to consider the breed of dog when choosing a puppy for many reasons including potential genetic orthopedic problems. Hip dysplasia is typically a problem for large, stocky dog breeds. Small dogs and lean, slender breeds such as sighthounds rarely develop hip dysplasia. If you have settled on a breed that has an issue with hip dysplasia, be aware of the certification process of the parents. The Orthopedic Foundation of America publishes statistics on affected breeds. These may be viewed at: http://ofa.org/stats_hip.html

Other than selective breeding, it is possible to manage other factors in hip dysplasia development when raising a predisposed puppy. This may help mitigate genetic issues.

Nutrition

Nutritional factors are very important in the development of hip dysplasia. For example, it has been popular to try to nutritionally “push” a large breed puppy to grow faster or larger by providing extra protein, more calcium, or even just extra food. Practices such as these have been disastrous, leading to bones and muscle growing at different rates and creating assorted joint diseases of which hip dysplasia is one. One study showed that when puppies of hip dysplasia prone breeds were allowed to free feed, two thirds went on to develop hip dysplasia while only one third developed hip dysplasia when the same diet was fed in meals. Another study showed German Shepherds were nearly twice as likely to develop hip dysplasia if their adult weights were above average. Studies such as these have led to the development of puppy foods designed for large breed puppies, where the optimal nutritional plane is lower than for small breed puppies. After puppyhood, maintaining a lean body condition seems to be very helpful in mitigating arthritis signs.

Exercise

Exactly what the proper preventive exercise regimen might be is yet undefined. One study showed that puppies had an increased risk for hip dysplasia if they were allowed to freely run up and down stairs before age 3 months. Decreased risk was found in puppies allowed off leash exercise (such as in the back yard) before age 3 months.

Neutering Age

There is some controversy about the effect of spay/neuter before puberty. Male dogs rely on testosterone to stop bone growth and early neutered males will grow taller as their bones are grow for a longer period if testosterone is removed early. This may lead to a predisposing disparity in the growth of bone and muscle. There appear to be predisposing hip dysplasia factors for early spay as well assuming the dog has the genetic predisposition. How much added predisposition comes with early spay/neuter and to which breeds remains of great controversy. In one study looking into this, it was found that neutering before age 5.5 months was associated with a 6.7% incidence of hip dysplasia while neutering after age 5.5 months was associated with a 4.7% incidence of hip dysplasia.

HOW CAN I FIND OUT IF MY DOG HAS HIP DYSPLASIA?

There are two reasons to pursue testing: to explain a dog’s discomfort/rear weakness or to screen a dog for breeding purposes. If a dog is not going to be bred and is not in any apparent discomfort, there may be no benefit to looking at the conformation of the bones in a radiograph except possibly to look back at a future time to get a sense for progression of bony changes.

|

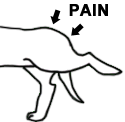

The first step in diagnosis is an examination. Your veterinarian will likely extend the dog’s hind leg backward to check for pain. (Hip dysplasia causes pain on hip extension.) The dog may be asked to walk around to possibly demonstrate the hip swivel. Another test involves having the dog lie on its back with a hind leg perpendicular to the body. As the leg is moved away from perpendicular to the body, a dysplastic hip will generate a “pop” as the femoral head slips to the center of the acetabulum. This “pop,” which can be felt if one’s hand is resting on the hip during the exercise is called an “Ortolani sign.” You may hear this term used as hip dysplasia is discussed.

|

(original graphic by marvistavet.com)

|

Ortolani Demonstration

(Video credit: Southpaws Specialty Surgery for Animals PTY LTD)

The true confirmation of hip dysplasia comes with radiography. The dog must be radiographed on his or her back with both legs positioned straight down. This is a painful posture to a dog with dysplasia so to get maximum cooperation from and comfort for the patient, sedation is needed. The seating of the femoral heads in the acetabular sockets is examined and the presence or absence of hip arthritis is assessed.

Below are two radiographs: normal hips on the left and dysplastic hips on the right. It is easy to see how the femoral heads are not well seated in their sockets in the dysplastic hips. This puppy actually has "subluxation" which means the hips are nearly out of the socket completely. Over time, the femoral heads will flatten and the sockets will become even more shallow. Bone spurs will develop around the joint capsule as the body attempts to stabilize the abnormal joint.

Normal hips

(Photocredit: Joel Mills via Wikimedia Commons) |

|

Hip Dysplasia in a puppy that does not yet have arthritis changes. Hip Dysplasia in a puppy that does not yet have arthritis changes.

When a dog is being assessed for hip dysplasia in an effort to qualify for breeding, this same radiographic view is submitted to the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals for evaluation. Obviously, if dysplasia is apparent, there is no need to submit the radiographs.

(Photocredit: Joel Mills via Wikimedia Commons) |

WHAT IS OFA REGISTRATION?

When purchasing a puppy, particularly one of a larger breed, often the parents will be listed as “OFA Good” or “OFA Excellent.” What this means is that the breeder has had the hips of the parent dogs certified by the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals. The OFA is an organization with a goal of reducing the incidence of hip dysplasia (though now it is also possible to obtain certification for elbows, thyroid function, and other issues). The idea here is that a dog for breeding can have radiographs taken at age 24 months. The radiographs are sent to the OFA for review by several independent radiologists where they are graded. Hips that are rated as “good” or “excellent” receive a registration number. Offspring of OFA certified parents would be less likely to develop dysplasia themselves, however, it is important to realize that a dog with excellent hips at age 2 may not have such excellent hips at age 5, 7, or 10. OFA certification is no guarantee that a dog will not develop hip dysplasia symptoms in the future and does not guarantee that the offspring will not develop hip dysplasia but, as mentioned, until DNA test for hip dysplasia is developed parental certification is the best we can do.

WHAT IS PENNHIP REGISTRATION?

Many people with potential breeding dogs do not want to have to wait two years for OFA registration. The University of Pennsylvania Hip Improvement Plan, developed by Dr. Gail Smith, allows for another way to predict if a dog will develop hip dysplasia. For PennHip certification, the veterinarian taking the radiographs must receive special training and special equipment is necessary. The pet is anesthetized and two radiographs are taken: one with the femoral heads “compressed” (pushed into the acetabula as far as they will go) and one with the femoral heads “distracted” (pulled out of the acetabula as far as they will go). A measurement called a “distraction index” is calculated from these radiographs, with the idea being that a tighter fitting hip (one allowing less distraction) is less likely to develop dysplasia. Each dog breed has a different range of distraction indices that are considered acceptable. Puppies can be certified as young as 16 weeks of age with this system.

|

View in Distraction

|

View in Compression

|

IS SURGERY THE BEST TREATMENT FOR HIP DYSPLASIA?

There are many surgical options for hip dysplasia and it is important to understand which patients benefit from which surgery. Some surgical procedures are controversial and some are not. All will entail a recovery period as well as expense. Often both hips need not be treated surgically; treating one hip is often enough to yield good results. Hip surgery is relatively expensive and a surgery specialist may be required depending on the procedure. If you are considering surgery for your dog, these are the procedures to know about:

- Femoral Head/Neck Ostectomy

This surgery is commonly referred to as the “FHO” and is best used for smaller dogs (50 lbs or less) or very active dogs. Here, the femoral head is cut off and removed, allowing the joint to heal as a “false joint” (just a capsule connecting the two bones but no actual bone to bone contact. If the dog is not carrying too much weight, a false joint is strong enough. If the dog is very active, a false joint will form quickly. The pet typically does not want to use the leg for the first 2 weeks but should at least be partially using the leg after 4-6 weeks. The leg should be used nearly normally after a couple of months. Many veterinarians are well experienced with this surgery and often a specialist is not needed. This surgery is typically substantially less expensive than the other procedures. For more details, visit our page on Femoral Head and Neck Ostectomy.

femoral head before FHO

(original graphic by marvistavet.com)

|

femoral head cut off after FHO

(original graphic by marvistavet.com)

|

- Triple Pelvic Osteotomy

This surgery is appropriate for young (age 8-18 months) dogs with dysplasia but without degenerative arthritis changes. This means that there is a window of opportunity for this surgery and if the dog develops arthritis or becomes too old, it will be too late for this surgery to be performed. In this surgery the ill-fitting acetabulum is essentially sawed free of the rest of the pelvis, re-positioned for a tighter fit on the femoral head, and then plated back into place.

Many times surgery on one hip leads to positive changes in the other hip so that surgery on the second hip is not necessary. Alternatively it is possible to do the TPO on both hips if it seems clear that ultimately both will need surgical correction. This is a surgery that requires a board certified surgeon or a surgeon with extensive orthopedic experience. After care involves a good 3-4 months of exercise restriction. No leashed walks except to go outside for elimination for 2 months.

The biggest problem with the TPO is determining whether the patient really needs it. If the dog is not experiencing hip discomfort at the time of diagnosis, he may not experience hip discomfort until he is an elderly dog and should he really have an invasive procedure early as a preventive? On the other hand, if he is having discomfort at a young age, the arthritis is likely to only get worse and early surgery could mitigate this tremendously. These are matters to discuss with the surgeon.

- Total Hip Replacement

This procedure is for dogs with degenerative hip changes already established. For these dogs, the best choice may be to simply replace the hip (or hips) with a prosthetic hip. This procedure may sound radical but it has been commonly performed for over 30 years in dog with great success. This is a highly invasive procedure obviously and infection must be avoided at all costs (no skin disease can be present in the skin over the hips, extra precautions for sterility are used). In other words, when complications occur they have potential to be disastrous. Complications have about a 10% incidence. Expect about 3 months of exercise restriction after this procedure. Usually only one hip receives surgery at a time. Often only one replacement is needed and the pet does well enough not to need surgery on the other side.

The hip on the right has been replaced with a prosthesis. The hip on the left still has substantial arthritis.

(Photocredit: Joel Mills via Wikimedia Commons)

- Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis

This surgery is performed on young puppies before age 5 months, so it is generally done as a preventive procedure before it is known if the puppy will indeed have dysplastic hips but after hip laxity has been detected. The pubic symphysis is the cartilage seem connecting the right side of the pelvis to the left side. As an individual matures, this cartilage converts to bone and the two halves of the pelvis fuse permanently. This surgery prematurely seals the symphysis which in turn results in rotation of the developing hip sockets into a more normal alignment. This is the same re-configuring as the the TPO above but instead of doing the reconfiguring with surgery, it is done by directing the puppies own bone growth. Note, the window is very narrow for this procedure so if a puppy is of a breed that is prone to dysplasia it may be worth screening radiographs around age 4 months even though no physical discomfort has developed. It may be worth having this preventive procedure while the puppy is still at an age to benefit from it.

(original graphic by marvistavet.com)

No matter which, if any, procedure is selected, it is important to get an idea of expenses, recovery procedure, and what is entailed from your veterinarian and from the surgeon before making a decision.

WHAT NON-SURGICAL TREATMENT IS AVAILABLE?

Non-surgical treatment of hip dysplasia is essentially the same as non-surgical treatment for any other type of arthritis. There are nutritional supplements to help repair cartilage, pain medications, and anti-inflammatory medications. Physical therapy and massage are also important and helpful in non-surgical joint therapy. There is no medical way to reverse or prevent hip dysplasia; the medications described are for pain management. For details please visit the Arthritis Center on this site.

Page last updated: 4/9/2025

|